Musings from Students of the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem

Posted on November 9, 2012 by Lauren Schuchart

This week’s Torah portion, Chayei Sarah, is chock-full of fascinating narrative. We’ve got the death (and life?) of Sarah, the purchase of the burial plot in Hevron, Rebekah by the well in what is the first shidduch (matchmaker) arrangement in the Torah, and of course, the burial of Abraham by his two sons, Isaac and Ishmael.

With all of these familiar names and “key players” in the Torah, I was strangely drawn to the narrative surrounding Abraham’s servant whose name is never actually mentioned in the text.[1]

With all of these familiar names and “key players” in the Torah, I was strangely drawn to the narrative surrounding Abraham’s servant whose name is never actually mentioned in the text.[1]

Here’s the brief background: In his old age, Abraham desperately wanted to find a wife for his son, Isaac. So, he sends his faithful servant to Abraham’s birthplace to find a wife for his son.

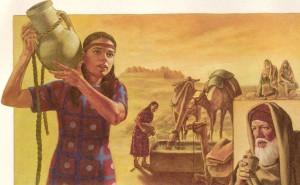

The servant obliged Abraham and went to Nahor, armed with lots of riches and bounty. When his servant arrived at his destination, the well[2], he said the following, in what is the first prayer for divine guidance in the Torah:

“O Lord, God of my master Abraham, grant me good fortune this day, and deal graciously with my master Abraham: Here I stand by the spring as the Daughters of the townsmen come out to draw water; let the maiden to whom I say, ‘Please, lower your jar that I may drink,’ and who replies, ‘Drink, and I will also water your camels’—let her be the one whom You have decreed for Your servant Isaac[3]. Thereby shall I know that you have dealt graciously with my master.”

Bereishit 24:12

Just as the servant finished saying the prayer, Rebekah, Isaac’s future wife, appears at the well. And what does she do? She offers the servant water, and then quickly draws water for the camels…exactly what the servant had prayed for!

This year at Pardes, I am taking the Jewish Educator’s Track class on tefillah (prayer). The class is specifically geared towards educators, and those who want to help others connect to prayer in a meaningful and significant way.

In the first half of the year, we explored different ideas and methods of prayer, the idea being that before we can teach prayer, we need to be “pray-ers” ourselves.

As someone who finds it difficult to connect to prayer, but actively strives to do so, I find this class fascinating. Lately, we have been trying to answer the seemingly simple question: why do we pray?

One answer to this question could be what we see at first glance in this week’s parsha: We pray because we believe that if we pray hard enough for something, we will receive it.

I’m very challenged by this explanation, because the reality that I see looks much different.

We can pray for significant things: health, happiness, well-being, family, love, etc. Unfortunately, our prayers aren’t always answered immediately, and sometimes, not at all. (Spoiler Alert: We even see this in the Torah, in the very next chapter, when Isaac prays for a child and it takes 20 years for that prayer to be answered (Bereishit 25: 21)).

So, why pray?

At closer inspection of the servant’s supplication, we get a better insight into the nature of his prayer. Abraham’s servant prays for “הקרה,” “good fortune,” or to “bring something good to pass”. He doesn’t ask God outright for a wife for Isaac, but rather, he asks for a sign. I would add, he also asks for the ability to recognize the sign when it happens.

So perhaps, this is why we pray. We don’t expect God to give us what we want, but to grant us the ability to open our eyes and see what is before us… to guide us in the right direction.

Lastly, I’d like to direct our attention to the “pray-er” in this situation, Abraham’s servant. In other places in the Torah, we see the prayers of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, etc. While the Torah stresses that they, too, are human, they are unarguably hugely important figures of their time, and of our tradition.

And here, we have Abraham’s servant, the first person we see in the Torah praying to God for divine guidance. We know very little about him, not even his name. But he, too, had the ability to speak with God, and even had his prayer answered.

From this story, we can derive something significant about prayer: no matter who we are—or where we are—in the context of the world around us, we have the ability to pray to God. While this might not be an answer to the complicated question, “why pray?” it certainly illustrates how the Jewish tradition feels about everyone having the ability to be in relationship with God.

Shabbat shalom!

[1] Commentators say that the servant’s name was Eliezer (from Bereshit 15:2).

[2] The well outside the city is where the women came out to draw water every evening (Bereshit 24:11). Later in the Torah, we see that Jacob and Moses also found romantic fortune at the well (Bereishit 29:9-11; Exodus 2:15-21) This must have been the place to go before the advent of JDate. Har-har.

[3] What’s with the camels? This can seem kind of strange through our modern lenses. Abraham’s servant brought 10 camels with him to the well, in order to give the camels as a form of payment to the woman’s father, in return for her hand in marriage (…er, let’s leave this one for now). The servant is looking for a woman that will not only serve him water, but will also water the camels, symbolic of overflowing hospitality and kindness.