Musings from Students of the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem

Posted on May 19, 2013 by The Director of Digital Media

X-posted from Eryn's blog post:

Eryn London (Summer ’06 & ’07, Community Education ’10, Year ’10-’11, Hourly ’11-’12) made Aliya from New Jersey three years ago. She is currently studying in the Manhiga Hilchatit Program at Midreshet Lindenbaum, which is a 5 year advanced Halacha learning program. Beyond learning she also runs activities at a nursing home, teaches theatre, and directs plays on the side.

Eryn London (Summer ’06 & ’07, Community Education ’10, Year ’10-’11, Hourly ’11-’12) made Aliya from New Jersey three years ago. She is currently studying in the Manhiga Hilchatit Program at Midreshet Lindenbaum, which is a 5 year advanced Halacha learning program. Beyond learning she also runs activities at a nursing home, teaches theatre, and directs plays on the side.

The brand-new Divrei Mahamal blog is written by the women that are currently studying in the Manhiga Hilchatit Program. The blog should be updated weekly by one of the women. The d’vrei Torah will be written in English, Hebrew or French.

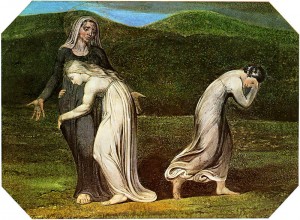

Naomi entreating Ruth and Orpah to return to the land of Moab by William Blake, 1795 (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

If your spouse died, your sister’s spouse died, your father-in-law died, and then your mother-in-law decided to go back to her land, and she told you to go back home, what would you do?

This is the story of Ruth and Orpah. Orpah decides to go back to her home town, and Ruth decides to follow Noami to Israel. According to the text, neither woman did anything wrong:

Return, my daughters, go for I have become too old to marry, that I should say that I have hope. Even if I had a husband tonight, and even if I had borne sons, would you wait for them until they grew up? Would you shut yourselves off for them and not marry? No, my daughters, for it much more bitter for me than for you, for the hand of the Lord has gone forth against me. And they raised their voices and wept again; and Orpah kissed her mother-in-law, but Ruth cleaved to her. (Ruth 1:12-14)

It seems that from the basic reading of the text that neither woman did anything that was extraordinary, neither positive nor negative. But the Rabbis seem to think differently. The Rabbis bring stories that depict Orpah as a very promiscuous and immoral person, for example:

The Name of one was Orpah, for she turned the nape of her neck (הפכה עורף) to her mother-in-law (Ruth Raba 2:9).

The night that Orpah left her mother-in-law she was intimate with one hundred men (Ruth Raba 2:20).

Ruth on the other hand, we are taught is a person who is modest and God-fearing.

“And the Second was Ruth” because she saw (ראתה) the words of her mother-in-law (Ruth Raba 9:4).

In Mesechet Shabbat 113a, she is depicted as being modest because she would bend down to pick up the sheaves of wheat (instead of just bending over). And in Midrash Tanchuma Behar, chapter 3, even though Naomi told her to dress up and put on perfume to seduce Boaz, she doesn’t get made up until she gets to the field so not to let someone suspect her of promiscuity.

So why are we so harsh on Orpah. What do we have to learn from the story of these two women who seem so similar, but the Rabbis feel the need to expound that they are complete opposites, one being good and one being bad?

Ruth and Orpah both start out in similar situations, but their lives become complete opposites of each other, based on one choice. I think that we can learn from the descriptions of the two women of the importance of thinking before we choose. That as a person, one can be good but if the community that one is associating with is not, it is very hard to stay as the minority. When we are looking to join a community or deciding what group of people that we want to associate with, we need to make sure that whatever we choose is a place that will allow us to become a greater version of ourselves.

As it says:

Nitai the Arbelite would say: Distance yourself from a bad neighbor, do not cleave to a wicked person, and do not abandon belief in retribution (Perkei Avot 1:7).