Musings from Students of the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem

Posted on January 30, 2012 by Naomi Zaslow

Tonight, my Night Seder chevruta – the amazingly talented Daniel Shibley – and I finished all 13 chapters of Ketubot in Mishna Masechet Nashim. To celebrate, we both gave short dvar’s, and had a small siyum (party).

Tonight, my Night Seder chevruta – the amazingly talented Daniel Shibley – and I finished all 13 chapters of Ketubot in Mishna Masechet Nashim. To celebrate, we both gave short dvar’s, and had a small siyum (party).

When Shibley initially asked me to give a dvar on what we had learned over the last few months, I kind of balked at the idea. While I had enjoyed learning Ketubot, I wasn’t sure that I had any insightful thoughts (or any thoughts at all) on the tractate to share, beyond a few weak bar jokes. Tonight, When I stood in front of the shtender and gave my dvar, I was struck with what an amazing experience this whole thing is. There I was, expostulating on a Mishna that we had been working on for months, when in September I had never learned a Mishna before in my life. Cool is an understatement.

/// Ketubot ///

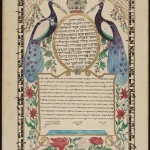

I initially started studying Mishna Ketubot because a lot of my friends are getting married. Like, a ton. Every day, my facebook feed is flooded with high school and university friends’ engagement announcements. And with Jewish weddings come gorgeous, ornate Ketubot, gold foiled, emblazoned with ani-le-dodi-ve-dodi-le, with a jerusalem skyline embossed across the bottom.

While this is all fine and good in a hiddur mitzvah kind of way, I was curious: what are these Ketubot really about? So, as it turns out, Ketubot are contracts. They are about money, money, and more money – with a dash of personal worth and responsibility. The tractate opens with differentiating between different types of women and how much they are worth in their Ketubot – from the convert to the captive, the virgin to the widow, each case is different. A ketuba essentially fulfills two purposes: fleshing out the responsibilities that a man has towards a woman in (and after) marriage, and to act as a financial deterrent to a hasty divorce.

In todays modern Ketubot-contracts, we often see vows that newlyweds make each other, outside of the financial realities of the classic Ketuba. Things like “I vow to cherish you forever. I vow to value you, unconditionally. I vow to do the laundry once a week and rub your feet.” It turns out that this is not so different from our classic Ketuba, which spells some of these personal vows out for us in a handy, hetero-normative way:

A man is required to provide his wife with food, clothing, sexual relations, to ransom her should she be taken captive, and to heal her should she become sick.

A woman is required to grind, bake, launder, cook, work in wool, nurse their child, and make his bed. To quote R’Gamliel, idleness leads to dullness – a prime example of humor in the Mishna!

At first, I struggled with this division of labor-vows. I don’t even make my own bed now, and you want me to be responsible for someone else’s’ – and his wool?! But maybe we can read it in an egalitarian way: what if the Mishna is really saying that ultimately, marriage (or any relationship – even a hevruta relationship!) is a chance to be OKAY with depending on someone else; that it allows us to recognize our our strengths and weaknesses in relationship to our partners. Relationships are opportunities for us to work with others, to see another point of view. One person should not be be solely responsible in all manners, because, after all, no one can do everything.

So, just a short bracha as we go into the second semester and build new relationships – may we realize that all of our relationships, in learning and love, are partnerships, where we bring in our strengths (whether they be wool dying or ransoming captives) and feel comfortable asking for help when we need it.