Musings from Students of the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem

Posted on February 28, 2012 by Barer

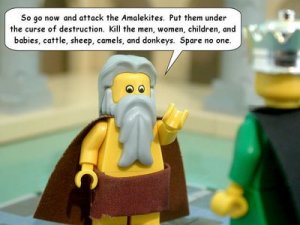

To the consternation of many around the world, there has been heightened tension around talk of some sort of war starting between Israel/US and Iran. With Parshat Zachor only a few days from being read in shuls (synagogues) around the world, it would behoove all of us to consider what kind of relationship we wish to have, as Jews, with the Amalek of our times. Amalek is portrayed in Jewish texts as our absolute enemy, to the extent that Jews are positively commanded to commit genocide against this people (though the Tanach claims that this has been accomplished; see Chronicles I 4:41-3). A more modern reading of this aspect of Jewish identity is to see Amalek not as a distinct people, of whom the guilty and the innocent must all be killed, but rather as the embodiment of the closest any people can come to absolute evil throughout the generations. On this reading, the common understanding that Haman, the villain of the upcoming holiday of Purim, as well as Hitler, Stalin, and now (as argued by many) Ahmadinejad, are all ‘descendents’ of Amalek, makes more sense.

But do we really want to keep as a core part of our Jewish identity the idea that we must constantly remember our hatred of other people, even if they perpetrated terrible crimes against us or other people? Daniel Roth, in Peace and Conflict, made the point that the reason tensions – at least in the media – are escalating at the moment between Israel and Iran is because each sees the Other as their Amalek, and this means that both are of the opinion that ‘we do not really want to know your story; you are just pure evil.’ Violence, or at least deep hatred, seem almost inevitable when parties to an intrenched conflict do not even make an effort to understand the other. I think that an important starting point to changing the worrying direction of recent developments is to try to understand that both (major) parties to this conflict see each other as their Amalek, as a live example of (near-)pure evil in the world. From that realization, the educational goals seem clear – instead of speaking about a commandment to hate Amalek, why not encourage shuls to broadcast the message that if we want to avoid the first war where nuclear weapons on both sides seems to be the major focus of the war, we ought to direct our energies towards understanding why a group of people can hate us so much?

Of course, hatred of Jews is an extremely touchy subject, with Iran being simply the most recent example. Admitting communally that Jews and Jewish values can be hated without that hatred automatically being equated with antisemitism would take a herculean effort. I present for your consideration a potential slogan of sorts in trying to think about these complex, hyper-modern concerns:

“The hatred of Jews and the Jewish national home by people whom history has adjudged to be comprehensively evil suggests a couple of obvious political lessons, leaving the theological lessons for another day: Good people should take the hatred directed at Israel by evil people as a sign that maybe Israel’s basic cause is just. Israel and its supporters should understand that such enmity reflects well on their cause, and they should do whatever possible to guarantee their behavior could never be seen as analogous to the behavior of their enemies.”