Musings from Students of the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem

Posted on February 22, 2013 by The Director of Digital Media

Please enjoy this Dvar Torah by Mordechai Rackover (PEP '03)!

Mordechai Rackover is a Pardes Alum, a member of the PEP 3rd Cohort. He currently lives in Providence, RI with his wife Nechama Lea and their four kids. He is the associate university chaplain for the Jewish community of Brown University and the Rabbi of the Brown RISD Hillel Foundation He can be reached at mrackover at gmail dot com or on twitter @mrackover

Mordechai Rackover is a Pardes Alum, a member of the PEP 3rd Cohort. He currently lives in Providence, RI with his wife Nechama Lea and their four kids. He is the associate university chaplain for the Jewish community of Brown University and the Rabbi of the Brown RISD Hillel Foundation He can be reached at mrackover at gmail dot com or on twitter @mrackover

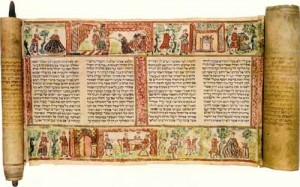

The Book of Esther, the Megillah, was my first Biblical love. I had opportunity to delve into it as a McGill undergrad prior to my first yeshiva experiences and discovered that it is a brilliant text. The Megillah is balanced and suspenseful, sacred and absent of God, deadly serious and filled with [ribald] humor. In this short essay I want to show that an essential factor in the reading of the stories of the Megillah is the obedience and disobedience of the characters. We have been trained, as it were, to look for obedient God-fearing Biblical characters as role-models. But, a closer reading, will show that disobedience is often a critical positive shaper of the unfolding biblical narrative.

The Book of Esther, the Megillah, was my first Biblical love. I had opportunity to delve into it as a McGill undergrad prior to my first yeshiva experiences and discovered that it is a brilliant text. The Megillah is balanced and suspenseful, sacred and absent of God, deadly serious and filled with [ribald] humor. In this short essay I want to show that an essential factor in the reading of the stories of the Megillah is the obedience and disobedience of the characters. We have been trained, as it were, to look for obedient God-fearing Biblical characters as role-models. But, a closer reading, will show that disobedience is often a critical positive shaper of the unfolding biblical narrative.

As children we were taught that the Megillah was full of women. There was, after all, a beauty pageant; Miss, soon to be Mrs, Persia! These were all the beauties of the land. As we’ve grown up we have come to understand that these women were exploited, afraid and pressed into a demeaning service wherein you could only gain notoriety by being the most memorable purveyor of sexual favors to a lecherous king.

But, in fact, we only have three named female characters, Vashti, Esther and Zeresh. Vashti, in a modern revisionist reading, has become a folk heroine for her obstinate refusal to give in to the king’s debased request. Esther, the Jewess, has always been cast was the heroine, after all, she brings deliverance to the Jews. Zeresh, the wife of Haman, has been considered a villain due to her association with her husband the chief antagonist of the Jews.

Vashti is the person who sets the story in motion. Asked to come before the drunken king and courtiers she refuses. Whether or not she was to be dressed or only adorned with her diadem is a matter of debate. I like to read the Megillah as I was taught to read Shakespeare as a high school student. Always imagine that there are two audiences: the pit and the box seats. The box seats filled with the upper crust were at the Globe Theatre to watch the art and absorb the story. The pit, filled with the lower classes, were there to be entertained, not only by the performance but also by the double-entendres that Shakespeare was so expert at. So back to Vashti, when the king summons her to appear in her royal diadem we can read the command in two ways: 1) come only in your diadem or, 2) appear before me and wear your diadem so everyone knows you are queen as you parade in. Big difference.

Vashti is the person who sets the story in motion. Asked to come before the drunken king and courtiers she refuses. Whether or not she was to be dressed or only adorned with her diadem is a matter of debate. I like to read the Megillah as I was taught to read Shakespeare as a high school student. Always imagine that there are two audiences: the pit and the box seats. The box seats filled with the upper crust were at the Globe Theatre to watch the art and absorb the story. The pit, filled with the lower classes, were there to be entertained, not only by the performance but also by the double-entendres that Shakespeare was so expert at. So back to Vashti, when the king summons her to appear in her royal diadem we can read the command in two ways: 1) come only in your diadem or, 2) appear before me and wear your diadem so everyone knows you are queen as you parade in. Big difference.

The Rabbis of the talmud preferred the bawdier reading because it cast Vashti and Ahashverosh in a worse light. It fits into their inclination toward reading Biblical tales as black and white, villain and hero, (see also, Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esav). But, disturbingly, this interpretation has been so ingrained that the midrashim that explain her refusal have become the peshat that is taught to school children.

The Rabbis of the talmud preferred the bawdier reading because it cast Vashti and Ahashverosh in a worse light. It fits into their inclination toward reading Biblical tales as black and white, villain and hero, (see also, Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esav). But, disturbingly, this interpretation has been so ingrained that the midrashim that explain her refusal have become the peshat that is taught to school children.

Consider the stories as the rabbis tell them. Vashti refuses to appear before the king and his courtiers because she is suddenly struck by leprosy. Or her refusal is due to her sudden sprouting of a tail. This makes Vashti, the Queen of Persia, into a disgusting person whose vanity is the only thing that keeps her from appearing nude in front of a group of drunken men. The idea that this is taught to school children is disturbing in its own right, but, as can be discovered in contemporary divrei torah, this idea has also been transferred into a parable of Jewish modesty and sanctity in opposition to non-Jewish promiscuity and debasement.

The peshat is that Vashti refuses to obey her husband. The motivation for this refusal is derash. The most likely reason for a self-respecting person, let alone a queen, for refusing to accede is her feeling that she is being objectified. Her refusal is heroic – it is brave, courageous, and quite possibly a choice with existential repercussions.

Vashti’s disobedience of her husband is often compared to Esther’s obedience of Mordechai. She does what he says and hides her Jewish identity. This is a very disturbing component of the story. Mordechai, my namesake, is meant to be a stalwart representative of Judea and Judaism, but he and Esther are both named for Near Eastern gods. And when Esther becomes socially mobile she is told to hide who she really is. Mordechai seems to be an assimilationist.

Vashti’s disobedience of her husband is often compared to Esther’s obedience of Mordechai. She does what he says and hides her Jewish identity. This is a very disturbing component of the story. Mordechai, my namesake, is meant to be a stalwart representative of Judea and Judaism, but he and Esther are both named for Near Eastern gods. And when Esther becomes socially mobile she is told to hide who she really is. Mordechai seems to be an assimilationist.

So what’s peshat here? I think one way to read this is that Mordechai is deep into his identity as a courtesan and maintains, at the same time, a deep relationship to his Judaism. He of course refuses to bow to Haman but really we don’t know why. But, once his people are threatened, he awakens to his true identity and pushes Esther to do the same. Mordechai’s disobedience of Haman, Esther’s obedience of Mordechai and her subsequent disobedience of the king (she comes to him when she isn’t call to) are the key factors in the unfolding of the story. So Esther’s heroism is counterintuitive in that it is connected to disobedience as opposed to obedience.

Zeresh. Oh Zeresh. She’s a bit player for sure. But the great thing about Zeresh is that she is a truth-teller: “If Mordechai, before whom you have begun to fall is of Jewish stock, you will not overcome him; you will fall before him to your ruin.” She seems to be the most ‘religious’ character in the Megillah. She has some idea about Jews being special and she tells her husband. She does lie, she doesn’t curry favor, she just lays it out. Notice that Esther has to jump through all kinds of hoops to get the king to get to the point where she can tell the king the facts. Zeresh just speaks it straight out.

Zeresh. Oh Zeresh. She’s a bit player for sure. But the great thing about Zeresh is that she is a truth-teller: “If Mordechai, before whom you have begun to fall is of Jewish stock, you will not overcome him; you will fall before him to your ruin.” She seems to be the most ‘religious’ character in the Megillah. She has some idea about Jews being special and she tells her husband. She does lie, she doesn’t curry favor, she just lays it out. Notice that Esther has to jump through all kinds of hoops to get the king to get to the point where she can tell the king the facts. Zeresh just speaks it straight out.

While the Megillah is about seeing everything a little differently we have fallen into the trap of reading it the same way year after year. Is Vashti the folk heroine for the 21st century? I don’t really think so but at least she is someone with self-respect. Is Esther a pathetic assimilationist? We don’t have to read her this way but we should be conscious of the problematic of her behavior and that of her mentor Mordechai who sets her in a very precarious position. And, Zeresh, she is married to a terrible man. Long enough to give him a minyan of sons. She is certainly a flawed person for that. But I like to reserve a little space for her to be not so bad. In the two times that Zeresh is mentioned she comes in the same sentence with ‘kol ohavav’. The Hebrew could be literally translated as ‘Zeresh AND those that loved [Haman].’ If we read the text literally the Megillah, in its subtle and layered way is telling us that Zeresh saw the truth and wanted to be distant from her husband.

Purim is set up by the Megillah. And on Purim as much as we read the text we should also be reading ourselves. Turning the interpretive lens into a mirror. Along with the openness that the celebration brings we should be attempting – for good or for bad – to reinterpret our own actions and inclinations so that we can have greater clarity in our lives.

Gut Purim

P.S. I only know one rock song that has the name Esther and the word Armenian in it. Here it is: