Musings from Students of the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem

Posted on April 13, 2013 by Naomi Bilmes

From my blog:

I have Haredi cousins.

I did not know this until last Friday night, enjoying couch-conversation with one of said cousins before Shabbat dinner.

So many different types of Jews…

“So what do people in this neighborhood call themselves?” I asked, wondering (after seeing all the black hats and streimels) which sect of Ultra-Orthodoxy I had resigned myself to for Shabbat.

“Mostly Haredi,” she replied. “Some Hassidish and Chabad, but most people are Haredi.” She paused, then added, “I’m Haredi.”

What is “Haredi”? According to the Oxford University Press, Haredi is defined as: “a member of any of various Orthodox Jewish sects characterized by strict adherence to the traditional form of Jewish law and rejection of modern secular culture.” Therefore, I was very surprised to find out that my cousin works for a travel agency full-time and arranges flowers and does make-up on the side.

“I’m a do-er,” she said. “I can’t just be in school all the time. I have to be out there doing something for people.” She was speaking about herself in contrast to one of her older sisters, who is getting her Ph.D in philosophy and linguistics.

My cousin is 22 and has eight siblings: a twin brother, whom I also met last weekend, and seven older siblings, six of whom are married with children. The first thing I did after arriving at their house was gaze open-mouthed at all the family photos, wondering who, what, where, when, how do they remember all the names?

I soon learned who was who, although if you asked me now, I probably could name four of the nine children and zero of the grandchildren. I was further confounded by the fact that two of the toddlers, born very close to one another, ended up with same name: Uriel Shraga. To differentiate between them, the family calls one Uriel 1 and the other Uriel 2.

Although the family is quite large, last Shabbat was a quiet one. The 22-year-old twins were there, and their parents, which made for a cozy count of five.

On Friday night, the men went to shul while the women davened quietly in the living room. During the meal, we had the requisite fish and salad course and then the main meal, and I was surprised to see the twins (not the mother) doing the bulk of the serving, clearing, and cleaning up. They had also done a good portion of the cooking. The twins sat across from me, bantering hotly throughout the entire meal—mostly in rapid Hebrew that I strained to understand. They switched effortlessly to English, though, my travel-agent cousin sporting an almost New York style English and my other cousin, who speaks less English on a daily basis, making his points through a thick, Israeli accent.

While the food was on the table, my male cousin and his father took off their black hats and suit jackets, but made sure to put them on again for birkat hamazon, the blessing after the meal. We sang Shabbat songs in between courses, being careful to sing only the songs classified for “Friday night”—and in their proper order. After the meal, everyone went for a walk in the cool, night air—but exhaustion put me straight to sleep instead.

The room I stayed in was full of books: Tehilim (Psalms), various commentaries on the Torah, books of Jewish law and philosophy, the occasional novel, and a slim volume entitled, “The Tzniyus Book,” a treatise on female modesty which I felt obliged to read on Shabbat afternoon. Beneath my mattress were two other mattresses, to be spread out on the floor of the main room (or on the floor of the sukkah) when all the grandchildren come to stay. The room had a heavy door that shut out all noise and light; the room is a safe-room, where the family goes in case of a bomb threat. I slept peacefully, however; how could I not, considering I was surrounded by the words of countless rabbis and concrete walls that would save me from the worst?

The room I stayed in was full of books: Tehilim (Psalms), various commentaries on the Torah, books of Jewish law and philosophy, the occasional novel, and a slim volume entitled, “The Tzniyus Book,” a treatise on female modesty which I felt obliged to read on Shabbat afternoon. Beneath my mattress were two other mattresses, to be spread out on the floor of the main room (or on the floor of the sukkah) when all the grandchildren come to stay. The room had a heavy door that shut out all noise and light; the room is a safe-room, where the family goes in case of a bomb threat. I slept peacefully, however; how could I not, considering I was surrounded by the words of countless rabbis and concrete walls that would save me from the worst?

I woke at 8, ready to go to shul with the matriarch of the family, my cousin Bayla. We headed out into the sunny morning and walked for about five minutes: we climbed stairs and more stairs, tunneled through an alleyway, then ascended again and entered the shul. We were in the “ezrat nashim,” the women’s section. To the naked eye, it was simply a room with white cloth-covered tables and shelves of books, but a closer look was in order. The tables were against a wall, the top half of which wasn’t solid. Every few inches was a metal bar, and behind the bars was a cloth curtain. When the curtain was lifted (which only happened rarely,) one could see that down below was another room – a room full of black hats, black suits and beards.

Hagbah: the only time we lifted the curtain

At first, I felt awkward and could not find a flow for my prayers. We were so high up that I couldn’t hear the man leading—how was I supposed to know what prayer we were up to? It turns out that, for the first portion of the service (p’sukei d’zimrah), no one technically “leads” so there is nothing to hear. This freedom to go at my own pace was initially disconcerting, but after a while, I realized that, for the first Shabbat in a long time, I had been able to recite all the p’sukei prayers. When the leader belted out “Shochen ad marom” (the beginning of the next part of the service) I was ready.

The service went quickly, but not so quickly that I couldn’t observe the women around me. Before the amidah (the silent heart of the service), the women moved away from the tables to create a space free enough to encompass their spirits. They cinched the curtain closed even more to shut out any distraction, and many of them were physically embodied by the words. The female crowd consisted of young girls, teenagers, and women of middle age. A huge gap existed where the 20- and 30-somethings should have been; I safely assumed they were occupied with, let’s say, a solid number of children. As for dress code, most women wore subtle colors: black, white, grey, navy, beige, and maybe even a little light pink. The shoe of choice was a black ballet flat with a bow on the toes, so my light brown, knee-high boots with blue, red, and white branded me an outsider (not to mention my turquoise shirt that peeked out from beneath my gray sweater). Most of the married women wore sheitels (wigs) rather than hats, and the unmarried girls wore their hair in low ponytails. In this community, the hair-bearing days for women are short; most young women wear their hair long, making the most of it until it has to be covered up.

The women streamed out of the shul before the service officially ended—otherwise, Bayla explained to me, the men would come out at the same time.

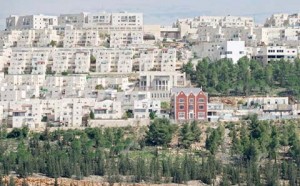

The hillside of Ramat Shlomo.

The brick building is the Chabad house.

After a quick kiddush in the kitchen of wine, nuts, and cake, Bayla took me on an hour-long walk around the neighborhood (it was only 11, so why not enjoy the sun before lunch?) The neighborhood, Ramat Shlomo, is built on a hill, yielding breathtaking views of the surrounding hills and the lower valley that contains central Jerusalem. Bayla explained to me that the neighborhood began construction in the 1980s, with strict building codes applied to the apartments and houses. Families from the surrounding areas could apply to live there – but they had to be of a certain religious level. Most of the streets were designated for Haredi families, while a few were saved for Hassidish and Chabad. One street was reserved for dati leumi (more of the Modern Orthodox type), but they are definitely in the minority. Despite the fact that almost everyone in Ramat Shlomo looks very religious, there are hundreds of nuances between the families. “There’s a lot of different people here,” Bayla said, “but we love everyone,” she added with a twinkling smile.

There are no cars at all on a Shabbat in Ramat Shlomo, which makes for a day that truly embodies m’nuchah, letting the simcha follow from there. I enjoyed a truly restful afternoon full of books, sunshine and quiet, and at 5pm I accompanied Bayla across the street to a Hassidish shul where a small group of women read Tehilim. The entire book of Psalms was divided into twenty little booklets, each booklet containing about five psalms. When you finished a booklet, you put it in the “done” pile and took another one. The goal was to get through all of the psalms at least once.

There are no cars at all on a Shabbat in Ramat Shlomo, which makes for a day that truly embodies m’nuchah, letting the simcha follow from there. I enjoyed a truly restful afternoon full of books, sunshine and quiet, and at 5pm I accompanied Bayla across the street to a Hassidish shul where a small group of women read Tehilim. The entire book of Psalms was divided into twenty little booklets, each booklet containing about five psalms. When you finished a booklet, you put it in the “done” pile and took another one. The goal was to get through all of the psalms at least once.

I sat quietly next to Bayla, putting the unfamiliar words through my lips. Every once in a while, I stumbled across a familiar psalm, or a phrase that I recognized from other places (such as modern a cappella songs). We did not speak to each other; we only whispered the words of the psalms and let them take us places. I went to a place of whispers and winds, letting my hungry soul be filled with what is good (Psalm 107:9).

I ended my Shabbat with some quiet meditation and prayer on the porch in the pink light of the setting sun. We then gathered for the third meal, which culminated in the longing songs of Yedid Nefesh (Beloved of the Soul) and Mizmor L’david (Psalm 23). For the first time in a while, Shabbat left me with peace, strength, and readiness for the week.

And now come the questions.

Was it odd to spend Shabbat with such religious people? Did I feel out of place and awkward? Was I angry that the women had such different religious roles than the men?

To be honesty, anger wasn’t really present in my weekend. As for oddity and awkwardness – well, there was a little. When I first arrived, I noticed that the bathroom I was supposed to use had only a toilet. The sink was in the public domain of the hallway, complete with a washing cup and towel. The same held true in the bathroom at the shul: no sinks in the bathroom, only washing stations outside. The obvious fact that everyone does ritual hand-washing publicly after every use of the facilities, although minor in the grand scheme of religious practice, was enough to make me feel instantly an outsider. During all of Shabbat, I alternated between washing and not washing – it is not my usual practice, but I did not want to obviously flout theirs.

A splash of color

Despite my feeling of halachic insuffiency, I tried to find a balance between blending in A splash of color with the culture while still respectfully being my own Jew. I wore a black skirt and tights the whole time and kept my arms entirely covered, but I diverged from the gray-scale color scheme with which the rest of the neighborhood clothed itself. I wore my regular pajamas (a t-shirt and lounge pants), but kept my skirt and sweatshirt on over them until I climbed into bed. I asked curious questions at the dinner table (“Why do we sit halfway through kiddush?”), but spoke mostly to the women and didn’t look the men in the eye.

Over the 25-hour Shabbat, my initial tenseness melted into an enjoyment of my out-of-the-box experience. I didn’t judge and I didn’t feel judged (except on the bus, when I might have accidentally sat in the men’s section). I thanked Hashem for my love of observation – a trait that allowed me to feel no anger over my discomfort; rather, it allowed me to accept my surroundings and fully appreciate how these people live. They value family, they value Jewish learning, they value hospitality, and they value the sanctity of Shabbat. And that is a wonderful mindset with which to spend a weekend.

But I also need to live with another set of values: the study of literature, history and the arts; the willingness to grant women a larger ritual role even if I do not want it myself; the freedom to meet whomever I wish and learn from the outside world. But I will live my life and they will live theirs. Ideally, we can peacefully overlap.

Over Shabbat, we did not talk about Palestinians, the State of Israel, or the fact that I spend a lot of time with boys (none of whom I am going on shidduch dates with). What we did talk about, however, was Torah, Halachah, cooking, Pesach break, Eilat, making coffee, and what binds us all together: family.